A General History of South Africa and its Development since 1652

A simple timeline of events from 1652 – 2000s.

In the Beginning

The first hominids to live in Southern Africa were the San people. (Oakes, 1989) Evidence of their rock paintings are still present and their descendants, the Bushmen, are still present today and living off the land like those before them. (Oakes, 1989)

About 2000 years ago, some of the San turned to pastoralism and acquired livestock from the Bantu speaking groups migrating south. Five hundred years later, the Bantu lived on the borders of present-day South Africa and the northern Transvaal. There is also evidence that suggests they coexisted with the KhoiKhoi in the Eastern Cape. (Oakes, 1989)

Before the arrival of the Dutch, KhoiKhoi clans lived on the coastline, and San hunter-gatherers in the region were prominent throughout the western side of Southern Africa. (Oakes, 1989)

The Arrival of Jan van Riebeeck and the Dutch in 1652

The Dutch East India Company set up a station at the Cape in 1652 to provide fresh produce for their ships travelling to the East around Africa to Europe. (Ainslie, 1987) They were led by Jan van Riebeeck. (South Africa Foundation, 1993) In the decades to come, they moved into the interior, largely as ranchers.

In 1657, The first non-company farmers were granted land to enhance productivity. This started the first European community in Africa. The French Huguenots joined them in 1688 (This is South Africa, 1980). By about 1750, these groups had settled and opened up an area that was previously wilderness more than five times the size of Holland. (Ainslie, 1987)

Over time and in isolation, the Dutch, the Huguenots and others developed their language of “Afrikaans”, and social segregation developed between them and the indigenous inhabitants with whom they crossed paths in the interior. (Ainslie, 1987)

Their first proper interaction with the Xhosa was in 1770 when the ranchers met tribes that had settled next to the Great Fish River, about one thousand kilometres east of Cape Town. (Ainslie, 1987)

The Frontier Wars

For the next century, the Great Fish River remained the ever disputed frontier between the Xhosas and the Dutch, who fought no fewer than nine frontier wars. (Ainslie, 1987) The first of these wars began in 1779. (South Africa Foundation, 1993)

In 1795, British powers took over the Cape in a race against the French. It was then given back to Holland in 1803 but finally relinquished by the Dutch to Britain in 1814. (Ainslie, 1987)

Shaka Zulu

Around 1820, Shaka Zulu was the king of the powerful Zulu nation of the east – now KwaZulu Natal. They either eradicated or took control of many tribes in the surrounding regions. Escapees fled to the Cape Colony and the interior. (Ainslie, 1987)

Escaping to the interior was Mzilikazi and his followers, a rebel general of Shaka. Shaka’s impis gave chase and initiated a series of mutually destructive wars known as Mfecane or Difaqane west of the Drakensberg. (Ainslie, 1987)

These conflicts killed hundreds of thousands, depopulated landscapes and decimated entire tribes. (Ainslie, 1987) Shaka was assassinated by his brother Dingane for the Zulu throne in 1828. (de Beer, 1988)

The Great Trek

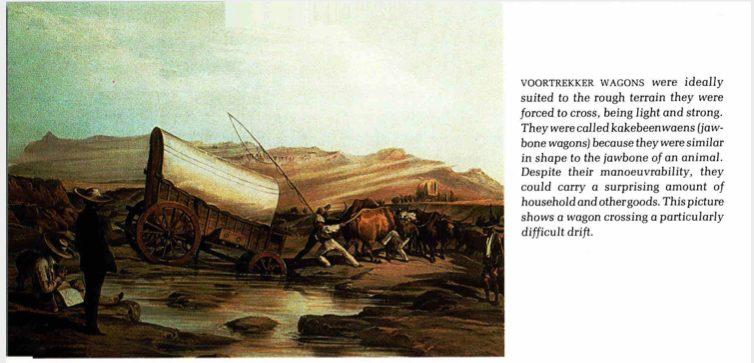

Between 1834 and 1838, around 6 000 Afrikaner farmers, fed up with British policy on the eastern border, set out across the Orange River. These Dutch travellers were known as Voortrekkers (Pioneers). They travelled across mostly de-populated, deserted wilderness areas, clashing intermittently with Matabele tribes who retreated across the Limpopo River into what is known today as Zimbabwe. (Ainslie, 1987)

Piet Retief, Dingane and the Battle of Blood River

In exchange for goods and services, Dingane agreed to grant parts of Natal south of the Tugela River to the Voortrekkers to form the Republic of Natalia. Chief negotiator and a leader of the Great Trek (McCord, 1952), Piet Retief and his unarmed colleagues were subsequently massacred by Dingane at a function held ostensibly to celebrate the land agreement in 1838. (Ainslie, 1987)

The Dutch had their vengeance at the Battle of Blood River in December 1838 when Voortrekkers and a few British settlers and their Zulu servants defeated and drove away the Zulu armies. (Ainslie, 1987)

Britain refused to recognise the Republic of Natalia and in 1842, deployed a military expedition to Port Natal – now Durban. Initially, the Voortrekkers fended off the British assault at Congella but later surrendered. Many Voortrekkers in Natal fled back across the Drakensberg towards the interior to reunite with their kin. (Ainslie, 1987)

The Battle of Boomplaats

In 1848, Britain took control of the area between the Orange and Vaal Rivers. They named it the Orange River Sovereignty. A large number of Voortrekkers then vacated across the Vaal River into the Transvaal. Those who remained behind were defeated by the British at the Battle of Boomplaats. (Ainslie, 1987)

During the early 1850s, the British did not pursue colonial responsibilities in Southern Africa. (Ainslie, 1987) Agreements were thus signed, and Voortrekker groups north and south of the Vaal River were granted independence in 1852 and 1854. This created the Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. (Ainslie, 1987)

Indians in South Africa

The modern South African Indian community is largely descended from Indians who arrived in South Africa from 1860 onwards. They were transported as indentured labourers to work on the sugarcane plantations of the Natal Colony. (Pillay, 2019) In total, approximately 200,000 Indians arrived as indentured labourers over a period of 5 decades, later also as indentured coal miners and railway workers. (Pillay, 2019; Mukherji, 2011)

A large percentage of indentured labourers returned to India following the expiry of their terms. Former indentured labourers who didn’t return to India quickly established themselves as an important general labour force in Natal, particularly as industrial and railway workers, with others engaging in market gardening, growing most of the vegetables consumed at the time. Indians also became fishermen, worked as clerks in the postal service and as court interpreters. (Pillay, 2019; Mukherji, 2011)

The remaining Indian immigration was from passenger Indians, comprising traders and others who migrated to South Africa shortly after the indentured labourers, paid for their own fares and travelled as British subjects. (Pillay, 2019; Mukherji, 2011)

Passenger Indians, who initially operated in Durban, expanded inland to the South African Republic (Transvaal), establishing communities in settlements on the main road between Durban and Johannesburg. (Pillay, 2019; Mukherji, 2011)

Diamonds in the Northern Cape

Diamonds were discovered in the Northern Cape in 1867 which brought many people from across the globe seeking their fortune. The British, some Griqua tribes, the Orange Free State, and the Transvaal contended for land ownership. Britain added the area to the Cape Colony. Furthermore, in 1877, they annexed the Republic of Transvaal, justifying this action by citing the Boer Republic’s alleged inability to govern itself or contain the Black rebels within its borders. (South Africa Foundation, 1993; Ainslie, 1987)

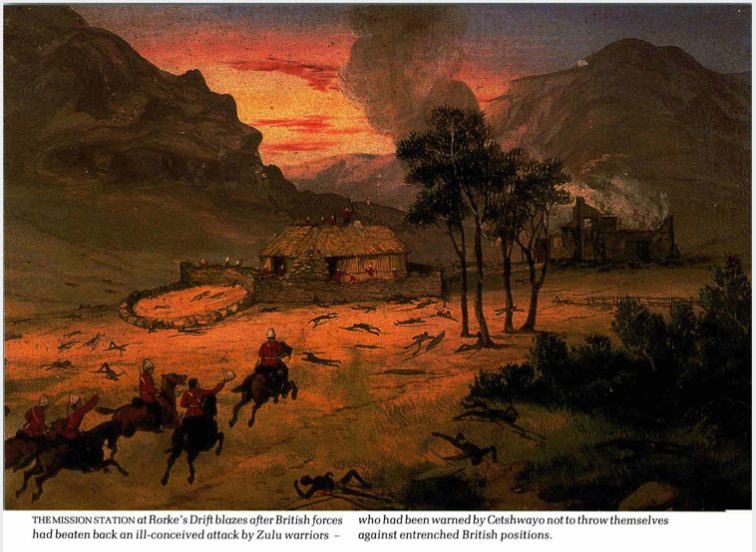

The Battle of Isandhlwana and Rorke’s Drift

The new Zulu King, Cetshewayo, assembled the Zulu army in KwaZulu Natal to pose a threat to both Dutch and British settlements. The British were devastated in 1879 at the Battle of Isandhlwana. Following the Battle of Rorke’s Drift, 104 English soldiers repelled 4,500 Zulu warriors and took the Zulu Capital of Ulundi. (de Beer, 1988; Ainslie, 1987) They divided Zululand into 13 chiefdoms and incorporated the rest into Natal in 1887. (Ainslie, 1987)

The First Anglo-Boer War

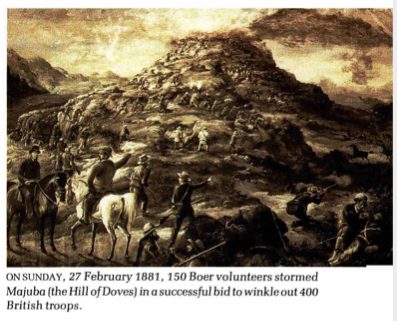

Under British rule, there was a large influx of English immigrants, which resulted in a strong sense of Afrikaner identity among the local people. Due to rising tensions, a war between the British and the Afrikaner republics began. (South Africa Foundation, 1993)

The First Anglo-Boer War was set in motion by the Transvaalers on the 16th of December 1880. They won 60 days later at the Battle of Majuba Hill. After an armistice, Paul Kruger became President of the Transvaal two years later. (de Beer, 1988)

Before 1882, immigrants to the Transvaal republic (“uitlanders”) could have full citizenship if they lived in the republic for at least a year and owned land. Once many more arrived, President Kruger passed a law that required five years of residence as opposed to one. (Millin, 1936)

Gold Rush and Prime Minister Rhodes

Gold reefs were discovered in the Witwatersrand in 1886 and attracted many more foreigners, or “uitlanders” from across the globe. (de Beer, 1988) Cecil John Rhodes became the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in 1890 (Oakes, 1988) These events gave rise to further tensions between uitlanders and the locals.

Mahatma Gandhi in 1894

In 1894, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi founded the Natal India Congress. He was a leader of the Indian cause in South Africa and united Asians in peaceful opposition to the pass laws of the Transvaal Government. As a practising attorney in Johannesburg, he arranged strikes and protests in Natal and became an icon of the Indian people in South Africa and later in India, this is how he got the name Mahatma (great soul) Gandhi. (de Beer, 1988)

The Jameson Raid of 1895

An arranged uprising of uitlanders coincided with a cross-border raid by 500 mounted police officers on the Transvaal in 1895. The invaders, led by Dr Leander Starr Jameson from the British South Africa Company, were routed by the Boers on the 2nd of January 1896. This failed raid drove Rhodes, founder of the British South Africa Company, to resign as prime minister. (de Beer, 1988)

Jan Smuts, future prime minister and proud Boer, once confessed that he had been a temperate admirer of Rhodes and even worked for him in the past. His admiration evaporated upon learning of the Jameson raid. (Millin, 1936)

The Second Anglo-Boer War

In 1899, President Kruger and the British discussed the rights of the uitlanders but President Kruger suspected that the real matter at hand was the control of the gold mining industry. (Schoeman, 2013)

English colonial leaders Sir Alfred Milner, governor of the Cape Colony, former prime minister Cecil Rhodes, British colonial secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, and mining syndicate owners, Sir Alfred Beit, Barney Barnato and Lionel Phillips advocated for the annexation of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. (Schoeman, 2013)

War broke out between the Transvaal and Orange Free State republics and Britain when President Kruger’s ultimatum regarding the cessation of British troop movements in his country was denied. The Anglo-Boer War that followed lasted from 1899 to 1902. Britain ultimately deployed over 450,000 troops against the Boer forces that never exceeded 35,000 men. (Ainslie, 1987)

Churchill’s Escape

Winston Churchill came to South Africa as a war correspondent in 1899 when the train he was on was ambushed and derailed by the Boers. Captain Haldane, who had invited him on the trip, and the surviving soldiers held off the opposition while Churchill rallied the unarmed passengers to clear the wreckage, using the train engine as a ram. (Schoeman, 2013)

Churchill, Captain Haldane and his men were captured by Louis Botha’s task force. They were taken to a school in Pretoria that had been converted into a prison. According to Churchill after a month in captivity he, Captain Haldane and another tried to escape, after hiding in an office, sneaking past sentries and scaling a wall. Churchill vanished into Pretoria but his companions did not follow. He then fled towards Delagoa Bay. (Schoeman, 2013)

General Botha and General Buller

Future prime minister, General Louis Botha and his men fought and beat the British at the battles of Ladysmith, Spioenkop and Colenso. (de Beer, 1988)

General Sir Redvers Henry Buller was the Commander-in-Chief of the Boer War until December 1899. Although he was an accomplished general, a veteran of the Ashanti and Zulu Wars and chief-of-staff in Sudan during the Khartoum campaign, replaced after being defeated in Colenso he was replaced by Earl Roberts. (de Beer, 1988)

The war was fought conventionally for the first year. Then the Boers deployed protracted guerrilla tactics. Eventually, the war was brought to an end by the British employing a scorched earth strategy coupled with the incarceration of the Boer women and children into concentration camps where 26,000 would die. (Ainslie, 1987; de Beer, 1988)

The End of the War

The Peace of Vereeniging was signed in 1902. (South Africa Foundation, 1993) South Africa was at the time divided into four colonies – the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange Free State, with three protectorates – Bechuanaland, Basutoland and Swaziland. (Ainslie, 1987)

The Union of South Africa

The Transvaal and Free State were granted responsible government in the years 1906 and 1907. Later, on the 31st of May 1910, the Union of South Africa was born when the four colonies would finally unite. (South Africa Foundation, 1993)

The Political Rise of Louis Botha and Jan Smuts

Botha was a believer in Afrikaner conciliation and worked diligently with Jan Smuts, military general, botanist, philosopher and politician. Botha’s South African Party won a majority in the first general election of the Union of South Africa, with Louis Botha (a Boer leader during the Anglo-Boer War) becoming the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa (1910–1919). Jan Smuts, also a Boer leader in the Anglo-Boer War, became Botha’s Minister of Defence (Heathcote, 1999). Botha was a war hero. He chose to support Britain in World War I. (de Beer, 1988)

The African National Congress Founded- 1912

The African National Congress was formed in 1912 in opposition to the Land Act, which stated, except in special circumstances, that people of colour could not own land in South Africa. After waiting for the British to intervene and moderation proved ineffective, the movement became more radical in its fight for the rights of black Africans. (Malherbe, 1986)

South Africa in World War I

The Union Defence Force overcame the German-occupied colony of South-West Africa and occupied the capital of Windhoek on the 12th of May 1915. They were subsequently involved with valour in campaigns across East and North Africa, France and Flanders. (Ainslie, 1987) See for example the great sacrifices of SA troops at Delville Wood in France.

Another daring soldier and general from the Second Anglo-Boer War, James Barry Munnik Hertzog created the National Party in 1914 and opposed supporting Britain in World War I. (de Beer, 1988) The alliance between the Labour Party and the National Party won the general election in 1924. (de Beer, 1988) Hertzog introduced many constitutional and economic reforms such as replacing Dutch with Afrikaans as one of South Africa’s two official languages in 1925 and flying a new South African flag incorporating the Union Jack in 1928. (Ainslie, 1987)

The electorate supported a programme that made the South African Party of Smuts and the National Party of Hertzog unite to solve the country’s economic struggles brought about by the global recession at the beginning of the 1930s. (Ainslie, 1987)

South Africa in World War II

The United Party was formed and led by General Hertzog. He proposed to remain neutral in the Second World War against Germany in 1939. The SA parliament rejected his proposal. (Ainslie, 1987)

After this, General Jan Smuts formed a new government and Hertzog re-joined the National Party. Once more, the choice to go to war caused tension between the Afrikaners and those of English descent. South African armed forces fought with distinction in the North African and Italian campaigns. Due to armaments and consumer goods no longer being imported, they commissioned SA factories to fill the gap, thus initiating the South African industrial revolution. (Ainslie, 1987)

After World War II

In 1944 Nelson Mandela joined the African National Congress. Mandela, Oliver Tambo and Walter Sisulu found the Congress Youth League. (de Beer, 1988) In 1948, Dr Malan’s National Party won the general election with the help of a large majority of Afrikaner voters. (Ainslie, 1987)

Most Afrikaners joined the National Party to protect their heritage and to assert economic independence from the British. (South Africa Foundation, 1993; de Beer, 1988)

The Beginning of Apartheid

The National Party introduced legislation that enforced what for many years had been existing segregation practices. “Apartheid” (Separateness) was actively implemented – total territorial, social and political segregation of people based on their race. (South Africa Foundation, 1993)

In 1960, the African National Congress was banned and operated without a legal voice until 1990 (South Africa Foundation, 1993). They became intimately associated with the South African Communist Party that had been banned in previous years. (Malherbe, 1986)

South Africa became a Republic on the 31st of May 1961 after Prime Minister, Dr H.F Verwoerd, withdrew his application from debates on South Africa’s internal policies at the Commonwealth Conference in London, earlier in March. (South Africa Foundation, 1993; Ainslie, 1987)

In 1962, Nelson Mandela was given a lifelong prison sentence after being found guilty of conspiracy to commit sabotage in the Rivonia Trial. (de Beer, 1988)

After years of opposition from black African rights groups and the economic interdependence of black and white classes in a modernising economy, Apartheid became increasingly unworkable. (South Africa Foundation, 1993)

Dr Verwoerd was assassinated in parliament in 1966. His successor as prime minister was B.J Vorster. He led the Nationalist Party to the most substantial majority recorded in South Africa, in November 1977. (Ainslie, 1987)

P.W Botha

P.W Botha replaced Vorster as president after he retired in 1978. President Botha quickly deployed new policies to address the high priority political challenges of the time. These were broadening the democratic base and defending minority rights. In 1984, these endeavours came together to form the new constitution and brought Coloured and Asian minorities into Parliament. (Ainslie, 1987; de Beer, 1988)

The End of Apartheid

On September 20th 1989, F.W de Klerk became President of South Africa and subsequently unbanned the African National Congress, The South African Communist Party and other of its subsidiaries in 1990. (de Klerk, 1991)

Between 1989 and 1994, over 300 years of domination ended when politicians united to create a non-racial constitution. Political power was removed from the white minority and given to the popular majority. On the 10th of May 1994, the presidency shifted to the Head of the African National Congress. (Thompson, 2008)

Before this, events almost destabilised efforts for peace when the previous head of the South African Communist Party and African National Congress, Chris Hani, was assassinated (Thompson and Berat, 2014) by a Polish SA immigrant who is still in jail in 2021.

South Africa 1994-1999

Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress became president in 1994 while countries worldwide lifted their sanctions. Then South Africa joined the British Commonwealth and passed the Restitution of Land Rights Act. (Thompson and Berat, 2014)

Nelson Mandela worked diligently to maintain peace in the nation. When he retired in 1999, Thabo Mbeki took over as president and the African National Congress won a substantial majority in the election once again. (Thompson and Berat, 2014)

References:

- Ainslie, A., 1988. This is South Africa. Pretoria: Publications Division of The Bureau for Information, pp.18-24

- De Beer, M., 1988. Who Did What in South Africa. Johannesburg: AD. Donker, pp.7,30-31,35,41-42, 73,84,92,98,101,115-117.

- de Klerk, W., 1991. FW De Klerk. 1st ed. Johannesburg: Jonathan Bell, pp.1,79-98.

- Heathcote, T., 1999. The British Field Marshals, 1763-1997. Barnsley: Leo Cooper.

- Malherbe, P., 1986. A Scenario for Peaceful Change in South Africa. 1st ed. Cape Town: College Tutorial Press, p.14.

- McCord, J., 1952. South African Struggle. 1st ed. Pretoria: J.H. de Bussy, p.39.

- Millin, S., 1936. General Smuts. 2nd ed. Glasgow: Faber & Faber, pp.56-57,232-233.

- Mukherji, A., 2011. Durban Largest ‘Indian’ City Outside India. [Blog] The Times of India, Available at: <https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/spotlight/personal-finance-for-millennials-understanding-credit-cards/articleshow/84408475.cms> [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Oakes, D., 1988. Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of South Africa. 2nd ed. Cape Town: Reader’s Digest Association, pp.11-12,20-25,165.

- Pillay, K., 2019. The Palgrave Handbook of Ethnicity. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.77-92.

- Schoeman, C., 2013. Churchill’s South Africa. 1st ed. Cape Town: Zebra Press, pp.15-16,62-63,70,72,81,89.

- Thompson, L., 2008. A History of South Africa. 3rd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, p.241.

- Thompson, L. and Berat, L., 2014. A History of South Africa, Fourth Edition. 4th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, p.xxvi, xxvii.

- South Africa Foundation, 1993. South Africa 1994. 1st ed. Cape Town: Galvin & Sales, pp.2-5.

- 1980. This is South Africa. Pretoria: Publications Division, Dept. of information, p.8.